Luther Leonard heard the voice of his radio exclaim, “Seattle’s going to the Super Bowl!”

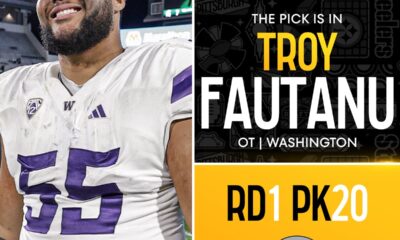

Down 16-0 at one point, in a thrilling come-from-behind overtime victory over the Green Bay Packers, Seahawks receiver Jermaine Kearse — Leonard’s friend and former college teammate — caught the game-winning touchdown in overtime.

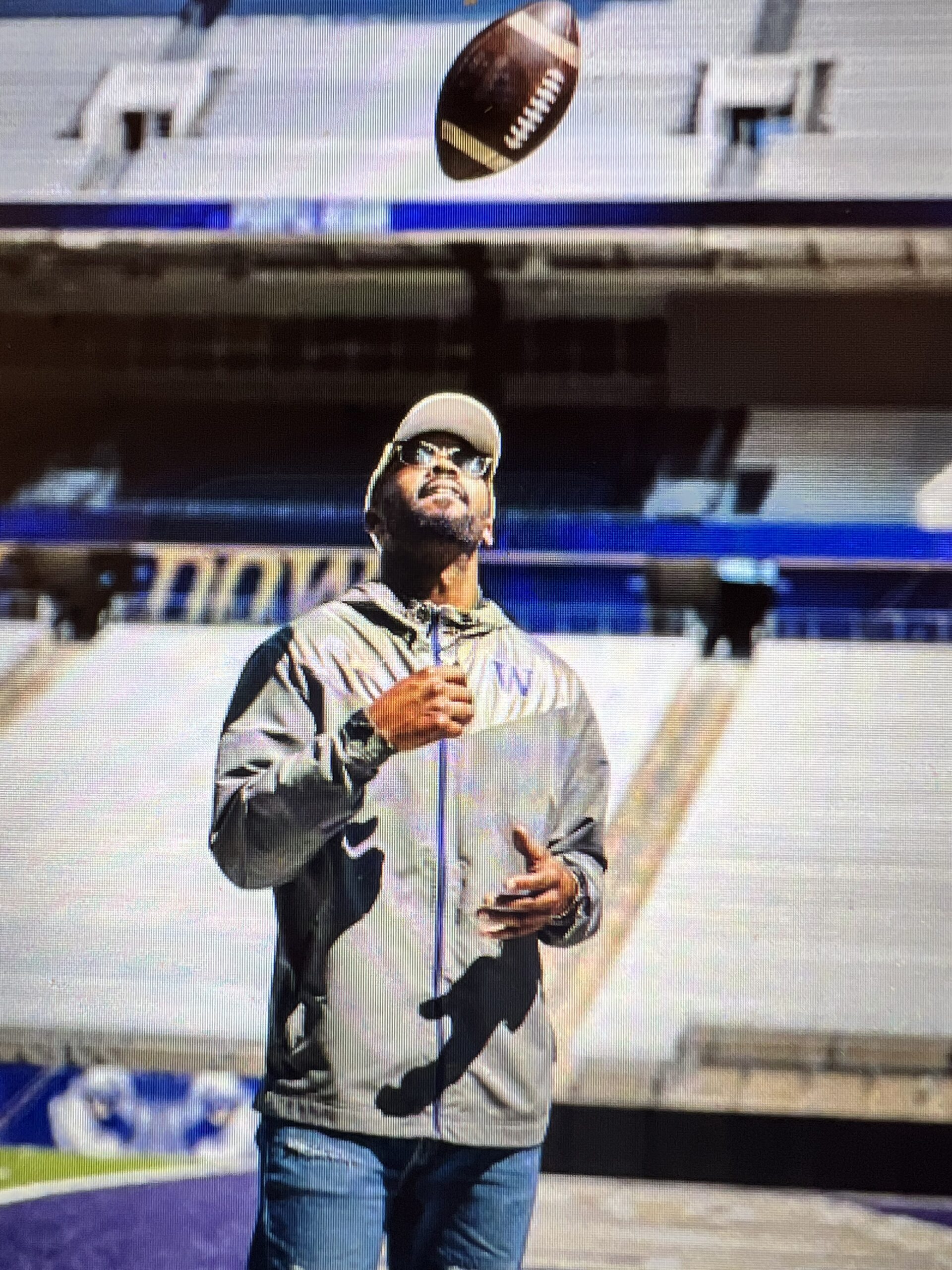

“That’s my boy! That’s my boy,” the former Washington Husky quarterback yelled while jumping up and down — albeit in his prison cell 177 miles away in Aberdeen at the Stafford Creek Corrections Center.

The two best friends were now miles away and worlds apart.

But nobody on D-Wing believed Leonard when he said that he and Kearse had been teammates and friends at the University of Washington.

Coming out of Evergreen High School, Leonard was the 13th best dual-threat QB in the nation in the recruiting class of 2008, in large part thanks to his running ability. Facing him in those days — with a football in hand — struck fear into teams’ hearts. In 2007, he led Evergreen to an 8-2 record, scoring over forty points in five contests, with his only losses being to Kennedy Catholic and Camas. The season before Evergreen saw just three wins, and Leonard’s star was on the rise.

He signed up to play for Tyrone Willingham and his hometown Huskies. He arrived on Montlake with the likes of Kearse, fellow Evergreen teammate Senio Kelemete, Chris Polk, Everrette Thompson, Alameda Ta’amu, Jordan Polk, Jori Fogerson, Greg Walker, Justin Glenn, and Cody Bruns, among others in the 2008 recruiting class.

But when UW went 0-12 that season, Willingham was subsequently fired and replaced by Steve Sarkisian.

“The new staff told me that I’d never play quarterback at the University of Washington,” Leonard recalled. “I was moved to the receiver room.”

As a dual-threat QB, Leonard’s feet were just as much of a weapon as his arm. However, he wasn’t quite fast enough as a receiver, and found himself at the bottom of the depth chart. He realized quickly that there’s a difference between being “QB fast” and “receiver fast.”

“I was the slowest guy in the receiver room,” Leonard said. “I could have transferred to Eastern but all I ever wanted to be was a Husky.”

He accrued no stats at Washington, with his GoHuskies.com bio containing a simple footnote referring to the 2011 season that reads: “Saw action in both the Utah and Stanford games.”

“You dream of going to the league,” he said. “You have all of these accolades but no real plan.”

However, July 1st, 2013, Leonard’s weapon of choice was no longer a football, but instead a gun.

“It’s such a juxtapose. A year before I was on scholarship at the University of Washington,” he recalled.

A true leader.

“Not knowing who you are once the helmet comes off, I had no clarity of vision,” he said. “In those dark spaces, when your back is against the wall–aint no coach, aint no mom, aint no dad, aint no system except the system you don’t want to be in.”

For the first time in his life, he became a follower, and on that first day of July he followed his aunt’s boyfriend into Bank of America branch in Newcastle, south of Bellevue, Washington.

“He said, ‘you have a 4-year degree, I don’t, and we have the same amount of money,'” Leonard recalled the words of Jeffery Pool.

Leonard was used to walking into hostile environments. Those included Pullman, Washington to play the Washington State Cougars, Eugene, Oregon to take on the Ducks, and South Bend, Indiana to face Notre Dame. The butterflies in his stomach were different as he found himself with a real-life weapon in hand — and could easily be shot if he encountered the police.

Just before entering the bank, he and Poole shared some final words and a bottle of water that he dropped on the ground like he’d done hundreds of times before on the sideline during games.

With an exhale to calm his nerves he pulled on a disguise for his face like he’d pulled down his helmet thousands of times. Leonard followed Pool into the bank and demanded cash, getting away with an estimated $47,000.

The got away pretty cleanly — except for one small detail. Area surveillance footage showed them both drinking from that discarded bottle before entering the bank.

“They found both of our fingerprints on the water bottle,” Leonard recalled. “They had us on video, too.”

They became known as the Big Top Bandits.

Pool, with his lengthy criminal record, was well-known to law enforcement in Texas and happened to be in Seattle on the run from Texas authorities. He was later traced to Leonard’s aunt’s house in Renton.

There, the police found Pool and Leonard and the weapons used in the heists — Pool’s handgun, and Leonard’s weapon of choice: a toy BB gun.

But, it wasn’t the preponderance of evidence against him that led to his downfall, or the fact that a lengthy trial of a college quarterback would draw unwelcome headlines, especially with him quarterback being a former Husky. Leonard simply wanted to take his punishment and restart his life as quickly as possible — so he pled guilty.

“I was embarrassed that I’d lived up to society’s low expectations of a young black man,” he said in an uncharacteristic deep voice. “And I had disgraced the University of Washington.”

In the purple and gold that he’d dreamed of playing in since childhood, he stood on the sideline for all but three total plays during his senior year. That wasn’t the payoff that he had been expecting since he was a kid.

“You think that you’re going to go to the league,” he said.

But it was this one play off the field that changed the course of his life.

After graduating from Washington, he returned to live with his aunt.

“After college, you find yourself right back in the situation that you think that athleticism would get you out of,” he reflected. “You have those four years year of flying across the country, staying in the best hotels; then you’re snapped back into reality when it’s over.”

Within 18 months of graduating from UW, he traded his jersey number, 83, that he’d worn as a receiver for his Washington Department of Corrections number.

He was arrested three weeks after the heist and found himself in prison a short time after.

“I was going to take my punishment,” he said. “I wasn’t supposed to be there.”

He wasn’t supposed to be in that bank, the courtroom, the jail cell.

“When I found out that I was going to prison I physically threw up. When you get recruited to the University of Washington it’s because you’re smart and you’re athletic,” he said.

Just one year earlier he’d been readying for his senior season at UW. He certainly had the brains. While he rarely saw the field, he did have his name pop up on the academic honors board several times throughout his time at Washington.

“In prison, you get to spend 23 hours a day with yourself,” he said. “You have to do the time and not let the time do you.”

Using that mindset, he treated his nearly two years behind bars in Aberdeen just like halftime in the Husky Stadium locker room. In other words, he regrouped.

Yes, his body was incarcerated, but not his heart, not his soul, and certainly not his mind. He knew that they hadn’t taken away his freedom—he knew that he’d given it away in a moment of weakness.

“No TV, no cell phone. You can reflect on your temperament, what you could have done better,” he said.

He scratched out his thoughts on his yellow notepad. The more he thought, the more he wrote, and the more he wrote the more profound his thoughts became.

“You gotta know yourself,” he said of how he began to rebuild himself. “There is an element of God, an awakening of in yourself that does take place.”

Alone in his prison cell, he said that God made a promise to him: “My life wasn’t over, it was just beginning.”

He managed to discover himself in prison and find freedom inside the prison walls.

“Behind bars, I found out that I’m much more than a football player,” he said. “I’m a thinker. I got recruited to play quarterback at the University of Washington. To have that happen you have to be smart.”

He began to put his mind to work again.

“I read books on economics, on business, on religion,” he said. “I listened to people’s stories from a genuine place of humility.”

Given multiple opportunities to point fingers at anybody else other than himself, Leonard won’t blame anybody but himself.

“Nobody put that gun in my hand,” Leonard said.

His thoughts that were jotted down on the yellow sheets of paper in his jail cell became his battle cry and he’s transformed them into songs like “Let Freedom Ring” and “Power to the People”.

He continues to write and produce his own songs and can be found tonight at 7:30 at South Hall at 1253 S. Cloverdale St. in Seattle. Leonard will be playing new material including “Crawl 2 Soar”, “Silver Spoon”, “King of Ports”, and “20/20 Vision”.

Part 2: Leonard Finds His Way Back, With a Little Help from a Friend